Few books manage to weave humor and horror as effortlessly as Orwell’s Animal Farm. Beneath its deceptively simple story lies a profound critique of power, propaganda, and the fragility of ideals. It is a razor-sharp satire, alive with humor, wit, and an unnerving resonance with the political dynamics of today. Orwell doesn’t just tell a story; he stages a play where each character embodies an archetype, transforming the farm’s descent into chaos into a timeless and deeply unsettling commentary on power and manipulation.

Much like my experience with Kafka’s Metamorphosis, the brilliance of Animal Farm unfurled itself long after I turned the last page. While Kafka left me questioning the boundaries of duty and selfhood, Orwell left me pondering power, propaganda, and the fragility of collective ideals.

The Propaganda Machine: Squealer and the Art of Spin

Among the richly sketched characters, Squealer stood out to me—not because I admired his cunning, but because he epitomizes the state-controlled media so prevalent in today’s world. Orwell captures his essence with such playful precision: a pig skipping from side to side, whisking his tail to distract and disarm his audience. I couldn’t help but laugh at the mental image, even as I recognized the chilling truth behind it.

Squealer’s talent lies in his ability to reduce complex ideas into palatable, often misleading, slogans—a tactic that echoes in the echo chambers of modern-day discourse. The way he manipulates facts, bends truths, and outright lies to maintain Napoleon’s power is uncomfortably familiar. Squealer’s insidiousness lies in his lack of conviction, shifting allegiances to serve those in power, whether Snowball or Napoleon.

Initially, Squealer appears as a mouthpiece for Snowball’s vision of Animalism, enthusiastically promoting its principles. Yet, as soon as Napoleon overthrows Snowball, Squealer seamlessly transitions into the enforcer of Napoleon’s tyranny, defending every decision with an unnerving mix of charm and false logic. This adaptability underscores his role as a symbol of broken media—a force not committed to truth or justice, but to self-preservation and the perpetuation of power.

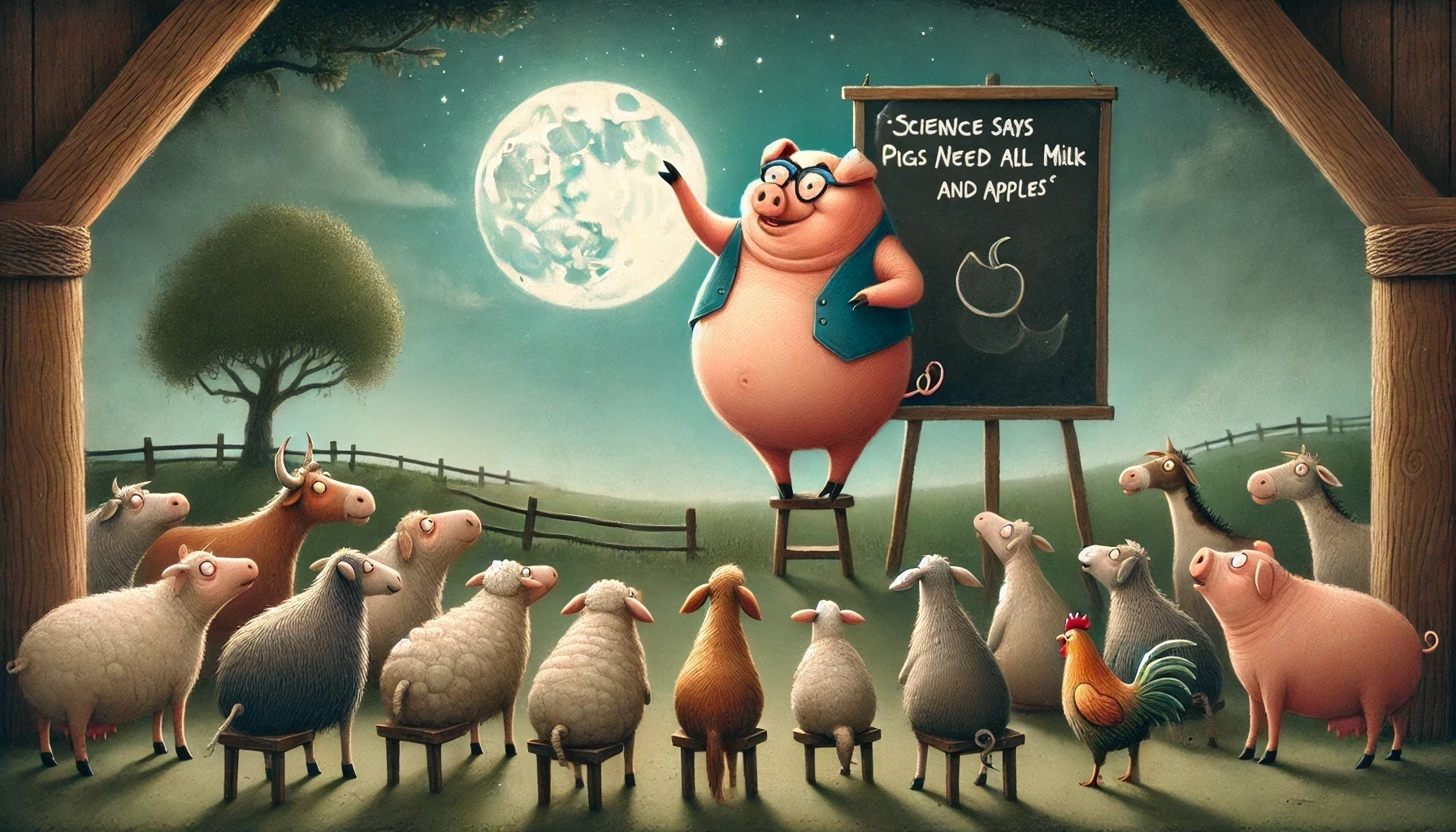

What struck me further was Squealer’s invocation of “science” to manipulate the animals. He uses it to explain why the pigs deserve the milk and apples, asserting that their consumption is a matter of scientific necessity. This struck a chord with me because it reflects a growing modern trend: how easily the educated class’s opinion can be swayed when something is stamped as “scientific” or dismissed as “pseudoscience.” Often too afraid or naïve to challenge what is presented as authoritative knowledge, people unquestioningly accept narratives cloaked in the veneer of science, much like the animals did. Orwell’s insight into the misuse of science as a tool of propaganda feels eerily relevant today.

Orwell’s portrayal of Squealer forces us to confront a disquieting question: how much of what we believe today is shaped by the squealers of our time? These agents of propaganda, like Squealer, thrive not on conviction but on their ability to manipulate, distract, and twist narratives to suit those in control. It is a chilling reminder of how essential it is to question the information we consume, even when it claims the authority of science, and to remain vigilant against the seductive power of propaganda.

The Sheep: Mindless Chorus of Misguided Activists?

If Squealer represents the propaganda machine, the sheep symbolize those who absorb it without question. Their chants of “Four legs good, two legs bad!” initially amused me, but their uncritical parroting soon took on a more sinister tone. These dimwitted followers, incapable of independent thought, are so easily manipulated that they can even be made to parrot opposing ideals without realizing the contradiction. A striking example is how, after a little brainwashing by Squealer, the sheep seamlessly transition to chanting “Four legs good, two legs better!”—a complete betrayal of the original tenets of Animalism. Their blind allegiance and malleability render them tools of the ruling pigs, who exploit their mindless repetition to drown out dissent and stifle nuanced debate.

Orwell’s portrayal of the sheep feels like a warning about the dangers of blind allegiance, no matter how righteous the cause may appear. The sheep aren’t malicious; they lack the critical capacity to see the larger picture. Loud, persistent, and easily swayed, their sloganism becomes a weapon, not of conviction but of manipulation.

What unsettles me most isn’t their fervor—it’s their failure to pause, reflect, and question the motives of those who lead them. Orwell captures the tragic irony of a group whose loyalty, though well-intentioned, ultimately enables oppression. The sheep’s role as enforcers of propaganda underscores the dangers of unthinking conformity, a lesson that resonates as deeply today as it did in Orwell’s time.

Boxer: The Tragic Hero We Can’t Follow

Boxer broke my heart. His unyielding belief in hard work and the simple motto “I will work harder” made him the noblest character in the book. Yet, it is precisely this naivety that seals his fate. Boxer’s unwavering trust in Napoleon is both admirable and agonizing. His relentless dedication and physical strength serve as the backbone of the farm’s achievements, but his inability to see through the deceit of the ruling pigs makes him a tragic figure.

Even in death, Boxer’s tragedy is compounded by exploitation. The pigs not only discard him unceremoniously but also spin a false narrative about his final moments. They fabricate a story claiming that Boxer’s last wishes were for the animals to continue working hard and adhering to the principles of “I will work harder” and “Napoleon is always right.” This chilling manipulation of his legacy turns his sincerity into a tool for furthering their control, cementing Orwell’s critique of how leaders exploit even the purest intentions for their gain.

As much as I admired Boxer’s honesty and dedication, I found myself uneasy at the thought of him as a potential leader. His goodness is unquestionable, but goodness without critical thinking becomes a liability. Boxer’s inability to question authority renders him vulnerable, and by extension, it makes those who look-up to him vulnerable as well. It’s an unsettling realization: we often demand our leaders possess a degree of cunning—not because we admire manipulation, but because we hope they will wield that cunning for the greater good. This paradox leaves me grappling with the uncomfortable truth that even the noblest of intentions require vigilance and discernment to withstand the corrupting forces of power.

The Power of Rewriting the Past

As the story unfolds, Orwell masterfully illustrates how history is rewritten by those in power. The original ideals of Animalism—the promise of equality and collective well-being—are gradually distorted, reflecting the pigs’ growing dominance. The foundational principle “All Animals Are Equal” morphs into “All Animals Are Equal, But Some Animals Are More Equal Than Others,” epitomizing the betrayal of the revolution. These changes, etched onto the barn wall, become so routine and insidious that the animals barely notice. Over time, the animals forget not only the specifics of the revolution’s original goals but also the very reality they once fought against.

This historical revisionism extends to the depiction of Jones’ rule. While the animals initially remembered the harshness of his reign in vivid detail, this memory becomes blurred over time, manipulated to serve the pigs’ narrative. Through relentless propaganda, the leadership ensures that Jones is always portrayed as a looming threat, a symbol of all-consuming tyranny. The animals, with little education and no access to objective truth, can no longer differentiate between the genuine horrors of the past and the exaggerated tales spun by Squealer and his ilk. Consequently, they endure their present suffering in the belief that it is better than the fabricated horrors of Jones’ era—even though their current reality may, in fact, be worse.

The erosion of collective memory becomes the pigs’ most potent tool of control, severing the animals’ connection to the revolution’s ideals. Orwell’s chilling insight lies in showing how the past can be sanitized, distorted, or completely erased to justify present power structures. By rewriting history, the pigs sever the animals’ connection to the ideals of the revolution, ensuring their compliance through fear and confusion.

The manipulation of history in Animal Farm is a grim reminder of how truth—when stripped of context and distorted by those in power—can be weaponized. As the animals lose their grip on the original vision of freedom and equality, they unwittingly submit to a new tyranny. It is a sobering reflection on the importance of preserving and revisiting historical facts. Without a collective memory rooted in unaltered truths, a society risks being manipulated into repeating the very injustices it once sought to overcome. Orwell’s critique warns us that vigilance over history is not just a responsibility but a safeguard for liberty and progress.

A Parody of Stalinism, Not Socialism?

Perhaps the most significant takeaway for me was Orwell’s nuanced critique. Animal Farm isn’t just a condemnation of communist or socialist ideals, as it’s often mischaracterized, but a sharp parody of Stalin’s regime and the corruption of revolutionary ideals. Orwell doesn’t vilify the principles of the revolution; in fact, there are moments when the animals genuinely thrive under collective effort. In the early, optimistic phase of the farm’s socialist movement, education was encouraged. Public debates were held, and democratic processes, like voting on motions, were embraced. It was a time when transparency in governance fueled collective progress and gave the animals a sense of empowerment.

However, this initial era of growth and cooperation gradually gave way to a darker phase, marked by dwindling transparency and the abandonment of education as a priority. The pigs, once advocates of equality, began exploiting the lack of education among the masses, manipulating them with ease. The shift from fostering critical thinking to fostering blind obedience epitomized the descent into tyranny disguised as equality.

It’s also crucial to note that Orwell doesn’t romanticize Jones’ time—his rule, a stand-in for crony capitalism, is portrayed as oppressive and exploitative. The satire doesn’t pick sides between systems – capitalist or socialist; instead, it zeroes in on the universal tendency of power to corrupt, irrespective of ideology. These cycles of hope, betrayal, and power form the crux of the narrative.

As someone who firmly believes in the principles of private property, the rule of law, and equality of opportunity—tenets foundational to a free-market society—I must acknowledge that my perspective is far removed from any sympathy for communism. Yet, Orwell’s message compelled me to set aside my personal biases and confront an important distinction: Animal Farm is not a critique of the ideals of socialism or communism themselves, but of the corruption and concentration of power that undermine those ideals. It is a cautionary tale about the dangers of any system, including ones I might favor, when power becomes unchecked and unaccountable. The erosion of education and the manipulation of history serve as stark reminders of how even noble principles can be distorted for personal gain. Orwell’s brilliance lies in exposing the vulnerabilities of all systems, urging vigilance against those who exploit them.

The enduring relevance of Animal Farm is its ability to reflect the flaws of any societal structure—political, economic, or social. It reminds us of the importance of safeguarding values like transparency, education, and collective progress against the corrosive effects of power. For me, it’s a sobering realization, but one that feels as urgent today as it was in Orwell’s time.

Concluding Thoughts

In the end, Animal Farm left me equal parts entertained and unsettled. Orwell’s ability to weave humor and horror into a tale of pigs and propaganda is nothing short of genius. It’s a book that lingers, its deceptively simple story unraveling deeper truths with each reflection. For an amateur reader like me, it’s a reminder of why Orwell’s work endures: his metaphors might be farmyard simple, but they cut to the bone. I’m struck by its layers, its ability to entertain, disturb, and provoke thought all at once.

For me, the book wasn’t just an enjoyable read; it was an invitation to reflect. On power. On trust. On the stories we tell ourselves to justify our beliefs. And on the importance of questioning, even when it’s uncomfortable. If you’ve read Animal Farm, I’d love to hear your thoughts—what struck you the most, and how do you interpret its relevance in today’s world?